One day in 1986, when I was working as a music writer for The Christian Science Monitor, I got a call from a representative at Channel 13, New York’s PBS station. He told me that PBS was going to do a Great Performances special and they would like it to be covered by the Monitor.

One day in 1986, when I was working as a music writer for The Christian Science Monitor, I got a call from a representative at Channel 13, New York’s PBS station. He told me that PBS was going to do a Great Performances special and they would like it to be covered by the Monitor.

“You’ll be interviewing Miles Davis,” he said. MILES DAVIS?!! Omigod! I’m gonna meet MILES!! I was flabbergasted, not just because I was actually going to get to meet the man himself, but because I’d heard that Miles never talked to anyone. The PBS guy went on: “You’re to pick up Miles at his apartment on Fifth Avenue and then take him to lunch at the Carlyle Hotel. We’ll send along one of our PR people to go with you. We’ll pick you up on Thursday at 3 p.m.”

OK, I thought. OK, yippee! I’m gonna meet MILES!!

On Thursday a black stretch limo came to pick me up at 3 p.m. on the nose. Angela, the PR rep, was sitting in the back when I climbed in. She was black, classy and no-nonsense. She said, “Listen, Miles will probably give us a hard time, so be prepared.”

I nodded, and guessed that she’d already been through this with some other reporters. The limo driver dropped us off in front of Miles’ building. We spoke to the doorman and told him who we were. He rang up Miles, who said there was no way in hell he was going to do any damned interview.

Angela grabbed the phone from the doorman. “Listen Miles. This is the time we set up and you agreed to it.”

I couldn’t hear what Miles was saying on the other end, but whatever it was, it took a long time. Angela looked at me and rolled her eyes.

Finally she said, “OK, OK, Miles, we’ll set it up for another day,” and handed the phone back to the doorman, who smirked.

Angela said she’d call the limo back, but I told her I’d take the subway home. She said she’d phone me to set up a new date. I knew they had to get Miles to cooperate for the TV special, so I went home and waited for her call.

And call she did, the very next day, so we trekked back over to Miles’ place. This time we actually made it up the elevator. Angela knocked on the door. Miles opened it with the chain on and peered out.

“No,” he said.

“What?!” said Angela.

“I said no. No interview.”

Angela put her nose about an inch from his and said, “Listen Miles, you’re fuckin’ with my job. I don’t fuck with your job, so what makes you think you can fuck with mine?”

Miles opened the door.

“OK, you got twenty minutes,” he barked in a gravelly baritone.

Miles was married to Cicely Tyson at that time, and their apartment was a big, open, sprawling, multilevel affair covered with gray carpeting. Cicely was out of town. All around the walls there were clothes racks. Miles’ clothes, which he fondly referred to as “my shit,” were hanging on them. These were the many imported outfits he’d had custom made by famous designers from around the world, and he didn’t want to keep them hidden away in any closets. They were on display for all to see, with a big full-length mirror in the middle. I remember when Miles’ album “Tutu” had been released a few months before, with a killer close-up of only his face, Miles’ disgruntled comment to the press was “It doesn’t show my shit.”

Miles was married to Cicely Tyson at that time, and their apartment was a big, open, sprawling, multilevel affair covered with gray carpeting. Cicely was out of town. All around the walls there were clothes racks. Miles’ clothes, which he fondly referred to as “my shit,” were hanging on them. These were the many imported outfits he’d had custom made by famous designers from around the world, and he didn’t want to keep them hidden away in any closets. They were on display for all to see, with a big full-length mirror in the middle. I remember when Miles’ album “Tutu” had been released a few months before, with a killer close-up of only his face, Miles’ disgruntled comment to the press was “It doesn’t show my shit.”

Angela and I walked in, and I pulled out my tape recorder.

“Ohhh,” groaned Miles when he saw it. I sat down next to him on the sofa and pulled out the mike. He moved back, then got up and walked away. I looked at Angela. She walked over to Miles’ clothes racks and started poking through his clothes.

“Yeah, yeah,” said Miles, perking up a little.

Miles was a style man. When all the other guys his age were still carrying the torch around the arena one more time playing bebop and standards, Miles was forging ahead, setting up rock rhythm sections behind his horn and wearing satin jackets and sequined pants on stage. Even though his trumpet playing never changed much, he still liked to inject it into new settings.

As jazz singer Eddie Jefferson sang in his lyric to Miles’ tune “So What”:

“About the clothes he wears…

his style is in the future…”

Miles was anything but old hat. He said:

“If you’re not keepin’ up with the times, you end up with ‘bell-bottom music.'” He beckoned to me to join him and Angela as they took a closer look at his wardrobe. His jackets and coats were made from exquisite fabrics and leathers, things trimmed with peacock feathers, shimmering with silver and gold threads or sparkling with tiny reflective black studs. He insisted that Angela and I try some things on. I picked a Japanese black suede coat painted with white designs.

“Shit, that looks almost as good on you as it does on me.” Miles hoisted up his baggy printed pants around his skinny waist. I was having a ball, but was starting to worry about the interview that I was supposed to be gathering for my editor. I knew I’d never get Miles to sit down and talk into the dumb tape recorder, so I said:

“Miles, I have a ten-piece band with a similar format to Birth of the Cool.” It just slipped out, because I didn’t know what else to say, and I wanted to make some kind of connection with him. Bingo. Miles smiled broadly, and said:

“Yeah, Birth of the Cool, really?”

Birth of the Cool, for those who may not know, was the nine-piece band Miles put together and recorded in 1949-50. It was, along with Gerry Mulligan’s Tentette, one of the bands I’d most admired when I was a kid, and was undoubtedly one of the things that led me to my forming my own mini big band many years later. Miles grabbed my hand and dragged me over to his Yamaha DX7 synthesizer, which was set up alongside the clothes racks where Angela was still busy trying things on.

“Do you wanna take a lesson?” he laughed. He played some chords, and then asked me to play a couple of my tunes. In an instant we turned from an uptight journalist grilling a famous legendary jazz trumpeter into just two musicians swapping ideas. Now that Miles was relaxed and feeling good, I said sheepishly, “Hey Miles, we were supposed to talk about the TV show, remember?”

“I haven’t seen it yet,” said Miles. “I don’t know how the idea came up. They asked me to do it. I probably won’t like it.”

“Why’s that, Miles?”

“Because what you see yourself doin’ doesn’t look the same as you think you look…you know what I mean? I’m not so sure I want to see it right away.”

Actually, when I got a chance to preview the show the next day, I was happy to see Miles looking quite fit, sipping mineral water and eating sugar free candies. His bout a decade before with various health problems, as well as injuries from a car accident, had kept him out of music for more than five years. I asked him about it in our “interview.”

“I was sick,” said Miles. “I was an alcoholic. I used a lot of coke. If I had kept on playin’ I’d be dead.” He told me he hadn’t thought about his music at all during that period, that he’d put it out of his mind, which reminded me of some years before when I’d stopped playing myself and didn’t even listen to music. When he finally did come back, though, he was ready for a fresh, new approach. But some of his fans, and even his colleagues, complained. They wanted the old Miles, the Kind of Blue and Seven Steps to Heaven Miles back again.

“It’s like clothes,” he said, pointing at the racks around the room. “Some people look wrong in these new clothes,” he said. “Music is the same way. I play styles. If it’s reggae, I play reggae. If it’s calypso, I play calypso—I don’t play the blues when I play ‘My Funny Valentine.’ When you play styles, you’ll always be up to date, but…I won’t force one style on top of another style. It’s like wearing a sweater over a tuxedo.”

I was intrigued by these remarks since, to me, his trumpet style hadn’t really changed. But when I stopped to think about it, everything he played fit in perfectly with the backgrounds he chose.

Then he stood up and said, “Look, musicians feel like they haven’t done anything if they don’t feel that ‘yes!’ when they play. That happens when you play off each other.”

Then he waxed philosophical and mused about whether some day it might be possible, by some electronic invention, to extract music from the air, music that had been played at some time in the past but had never been recorded.

“It’s out there somewhere,” he said, scratching his chin.

“How’re your chops, Miles?” I asked, wondering how he’d managed to make his comeback so quickly.

“I’ve finally got my tone back,” he said. “I sometimes hit a high note, but I don’t hit it like a trumpet player who plays high notes—I hit it like ptew!—like that, like a gun.”

He looked at his watch. Over two hours had gone by since Angela and I arrived.

“OK, your twenty minutes are up,” he growled. Then he smiled and kissed me and Angela on the cheek, and we were off. I was much happier with our casual chat than I would have been with a formal interview, and I wrote it up pretty much the way it went down, except for his frequent use of the S-word.

“Wow, I just met Miles Davis!” I thought, grinning from ear to ear.

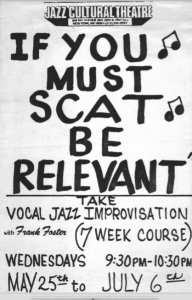

I met saxophonist Frank Foster (known as “Fos”) in the 80s at the Jazz Cultural Theater, a performance space founded by pianist Barry Harris. Harris gave classes there, and there were also classes taught by other musicians, including Frank Foster. I used to spend quite a bit of time hanging out there. I liked the vibe—it was funky and casual, and there were usually a couple of strung out musicians stretched out on the raggedy sofas in the entryway.

I met saxophonist Frank Foster (known as “Fos”) in the 80s at the Jazz Cultural Theater, a performance space founded by pianist Barry Harris. Harris gave classes there, and there were also classes taught by other musicians, including Frank Foster. I used to spend quite a bit of time hanging out there. I liked the vibe—it was funky and casual, and there were usually a couple of strung out musicians stretched out on the raggedy sofas in the entryway. Frank said yes, as a matter of fact, he was starting an arranging course the following week, so I joined up right away. Everything was fine at first, but then new people kept showing up every week and he’d go back to the beginning and start over. Also, he wasn’t teaching how to get the stuff down on paper, so I grabbed him after class and told him that the class wasn’t working for me and what I needed. He said, “Why don’t you come out to my house and I’ll give you a couple of private lessons.” Well, I was thrilled at the thought of that, because then I could have him all to myself and ask him all of my specific questions.

Frank said yes, as a matter of fact, he was starting an arranging course the following week, so I joined up right away. Everything was fine at first, but then new people kept showing up every week and he’d go back to the beginning and start over. Also, he wasn’t teaching how to get the stuff down on paper, so I grabbed him after class and told him that the class wasn’t working for me and what I needed. He said, “Why don’t you come out to my house and I’ll give you a couple of private lessons.” Well, I was thrilled at the thought of that, because then I could have him all to myself and ask him all of my specific questions.

I was living in Boston in the 60s and 70s (except for two years in Brazil in the late 60s). I don’t remember exactly when or how I first met jazz pianist Ray Santisi, although it was probably at what was then known as Berklee School of Music, where he was teaching. I didn’t have the financial wherewithal to enroll, so I would go over there and hang around, hoping to get to know some musicians or find a jam session.

I was living in Boston in the 60s and 70s (except for two years in Brazil in the late 60s). I don’t remember exactly when or how I first met jazz pianist Ray Santisi, although it was probably at what was then known as Berklee School of Music, where he was teaching. I didn’t have the financial wherewithal to enroll, so I would go over there and hang around, hoping to get to know some musicians or find a jam session.

One day in 1986, when I was working as a music writer for The Christian Science Monitor, I got a call from a representative at Channel 13, New York’s PBS station. He told me that PBS was going to do a Great Performances special and they would like it to be covered by the Monitor.

One day in 1986, when I was working as a music writer for The Christian Science Monitor, I got a call from a representative at Channel 13, New York’s PBS station. He told me that PBS was going to do a Great Performances special and they would like it to be covered by the Monitor.

Miles was married to Cicely Tyson at that time, and their apartment was a big, open, sprawling, multilevel affair covered with gray carpeting. Cicely was out of town. All around the walls there were clothes racks. Miles’ clothes, which he fondly referred to as “my shit,” were hanging on them. These were the many imported outfits he’d had custom made by famous designers from around the world, and he didn’t want to keep them hidden away in any closets. They were on display for all to see, with a big full-length mirror in the middle. I remember when Miles’ album “Tutu” had been released a few months before, with a killer close-up of only his face, Miles’ disgruntled comment to the press was “It doesn’t show my shit.”

Miles was married to Cicely Tyson at that time, and their apartment was a big, open, sprawling, multilevel affair covered with gray carpeting. Cicely was out of town. All around the walls there were clothes racks. Miles’ clothes, which he fondly referred to as “my shit,” were hanging on them. These were the many imported outfits he’d had custom made by famous designers from around the world, and he didn’t want to keep them hidden away in any closets. They were on display for all to see, with a big full-length mirror in the middle. I remember when Miles’ album “Tutu” had been released a few months before, with a killer close-up of only his face, Miles’ disgruntled comment to the press was “It doesn’t show my shit.”