“I am not a racist.”

“I am not a racist.”

It’s so easy for a white person like me to say that and think I actually know what I’m saying. But is it true? I was raised in a white community in Connecticut in the 1950s, and there were racists there. Even my mother was a racist, although she would never admit it. There was only one black family in our town at that time.

But when I was 13 years old, I fell in love with jazz and decided I wanted to play jazz piano. Suddenly, almost all my heroes were black people. I worshiped them, collected photos of them, and of course bought their records and listened to them. This opened up a whole new world for me.

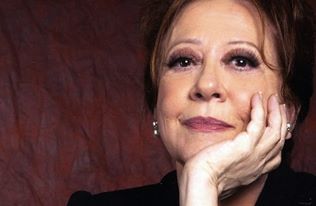

During the following decades, after I began to play professionally, I worked with many black players, and also had many black friends over the years. I had two marriages to black men, the first one back in the 1960s, when mixed marriages weren’t common at all. I continued to consider black musicians my heroes and mentors.

Then, in the 1990s, I moved to Brazil, to Rio de Janeiro, where there is a large black population. I felt right at home. I believed there couldn’t be anyone less racist than me. But recently I’ve been reading a book called Growing up Black, by Jay David, and it’s a serious wake-up call. The book is a collection of black childhood experiences, including some well-known names, throughout American history.

Reading the stories of what it was like for these people to grow up in America rattled me to the core. I realized that no matter how many black friends, colleagues, and even husbands I had, I would never, ever understand and certainly never feel what it was like to be a black person in America or anywhere else.

I used to take pride in the fact that I was “color blind.” Now I see it differently. It isn’t for me to “unsee” the blackness of my black friends, consciously or otherwise. To do so, I believe, would dishonor them. The best I can do in my ignorance is to love them with all my heart and soul.

I’ve never been particularly interested in politics, but this year, because of what’s going on here in Brazil, and especially because of what’s going on in my birth country, the USA, I can’t help getting involved along with everyone else.

I’ve never been particularly interested in politics, but this year, because of what’s going on here in Brazil, and especially because of what’s going on in my birth country, the USA, I can’t help getting involved along with everyone else. They talk about why they hate/love Trump, Hillary, Obama, and so on, and come across as certain that their views are correct. But these are just words, and to me everyone is missing a very obvious point.

They talk about why they hate/love Trump, Hillary, Obama, and so on, and come across as certain that their views are correct. But these are just words, and to me everyone is missing a very obvious point. I am not a fan of Donald Trump. I won’t go into why, because enough has already been said about why he is NOT a good person and is NOT qualified to be president of the United States of America. Just take any photograph of this man and look into his eyes. They’re dead, flat, mean. Do the same thing with photos of Obama or Hillary and you will see something quite different. Use your intuitive senses instead of simply spouting opinions or even facts. If you do this, you’ll see right into the essence of the person. For just a minute, let that be your guide instead of what you think you believe, what you’ve been told, what you’ve heard or seen in the news, or what you’ve seen on Facebook or read on Twitter. You might be quite amazed.

I am not a fan of Donald Trump. I won’t go into why, because enough has already been said about why he is NOT a good person and is NOT qualified to be president of the United States of America. Just take any photograph of this man and look into his eyes. They’re dead, flat, mean. Do the same thing with photos of Obama or Hillary and you will see something quite different. Use your intuitive senses instead of simply spouting opinions or even facts. If you do this, you’ll see right into the essence of the person. For just a minute, let that be your guide instead of what you think you believe, what you’ve been told, what you’ve heard or seen in the news, or what you’ve seen on Facebook or read on Twitter. You might be quite amazed. When I was a kid growing up in the 40s and 50s, it was not considered a good thing to be “shy.” The word “introvert” didn’t exist, as far as I know. In any case, I was a shy kid, a loner, and my mother worried about it.

When I was a kid growing up in the 40s and 50s, it was not considered a good thing to be “shy.” The word “introvert” didn’t exist, as far as I know. In any case, I was a shy kid, a loner, and my mother worried about it. The first time I saw someone practicing tai chi, I had no idea what they were doing. It was sometime in the 70s on the Boston Common, and I thought, “What on earth is that?” In later years I took a keen interest in Asian culture, and learned about martial arts, although I had no interest in studying them at the time.

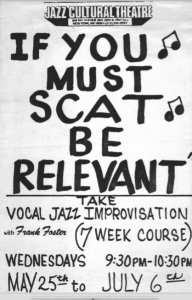

The first time I saw someone practicing tai chi, I had no idea what they were doing. It was sometime in the 70s on the Boston Common, and I thought, “What on earth is that?” In later years I took a keen interest in Asian culture, and learned about martial arts, although I had no interest in studying them at the time. I met saxophonist Frank Foster (known as “Fos”) in the 80s at the Jazz Cultural Theater, a performance space founded by pianist Barry Harris. Harris gave classes there, and there were also classes taught by other musicians, including Frank Foster. I used to spend quite a bit of time hanging out there. I liked the vibe—it was funky and casual, and there were usually a couple of strung out musicians stretched out on the raggedy sofas in the entryway.

I met saxophonist Frank Foster (known as “Fos”) in the 80s at the Jazz Cultural Theater, a performance space founded by pianist Barry Harris. Harris gave classes there, and there were also classes taught by other musicians, including Frank Foster. I used to spend quite a bit of time hanging out there. I liked the vibe—it was funky and casual, and there were usually a couple of strung out musicians stretched out on the raggedy sofas in the entryway. Frank said yes, as a matter of fact, he was starting an arranging course the following week, so I joined up right away. Everything was fine at first, but then new people kept showing up every week and he’d go back to the beginning and start over. Also, he wasn’t teaching how to get the stuff down on paper, so I grabbed him after class and told him that the class wasn’t working for me and what I needed. He said, “Why don’t you come out to my house and I’ll give you a couple of private lessons.” Well, I was thrilled at the thought of that, because then I could have him all to myself and ask him all of my specific questions.

Frank said yes, as a matter of fact, he was starting an arranging course the following week, so I joined up right away. Everything was fine at first, but then new people kept showing up every week and he’d go back to the beginning and start over. Also, he wasn’t teaching how to get the stuff down on paper, so I grabbed him after class and told him that the class wasn’t working for me and what I needed. He said, “Why don’t you come out to my house and I’ll give you a couple of private lessons.” Well, I was thrilled at the thought of that, because then I could have him all to myself and ask him all of my specific questions.

I was living in Boston in the 60s and 70s (except for two years in Brazil in the late 60s). I don’t remember exactly when or how I first met jazz pianist Ray Santisi, although it was probably at what was then known as Berklee School of Music, where he was teaching. I didn’t have the financial wherewithal to enroll, so I would go over there and hang around, hoping to get to know some musicians or find a jam session.

I was living in Boston in the 60s and 70s (except for two years in Brazil in the late 60s). I don’t remember exactly when or how I first met jazz pianist Ray Santisi, although it was probably at what was then known as Berklee School of Music, where he was teaching. I didn’t have the financial wherewithal to enroll, so I would go over there and hang around, hoping to get to know some musicians or find a jam session. Sam Rivers wasn’t my teacher in any “official” sense of the word. The great saxophonist/multi-instrumentalist simply glided into my young life with a proposal.

Sam Rivers wasn’t my teacher in any “official” sense of the word. The great saxophonist/multi-instrumentalist simply glided into my young life with a proposal. In my previous post, I said that I would write about six teachers who had changed my life. I’m going to do this in chronological order, and this is the first one (the only one still living):

In my previous post, I said that I would write about six teachers who had changed my life. I’m going to do this in chronological order, and this is the first one (the only one still living):